The Finnish artist Kimmo Schroederus shows us recent works

This exhibition by Kimmo Schroderus is currently on display at the Ciurlionis National Museum of Art in Kaunas, Lithuania.

The

exhibition opens in Bergen slightly ahead of the Arts Festival:

May

11th and will remain open till June 24. at Gallery 3,14

Annamari

Vänskä

Family values

”I need a man!” shouts an old fashioned Hollywood filmstar look-a-like Annie Lennox in her music video. However, it is not that obvious that it is a man she needs. She looks more like a strong woman with no intention or need to become a nice housewife. Ironically, looking at the sculptures of Kimmo Schroderus this is the tune that starts playing in my head. It is because Kimmo Schroderus (b. 1970) has provided a setting for a family by sculpting the basic fragments of daily life, for example, a bed, a table, two chairs, eleven mirrors and a car.

Longing

for family and homely environment is not something you would expect from

this tall and tattooed, masculine sculptor.

Before the modernity the public

and the private were inseparable. Family as a specific sphere of private

life was detached from the kin little by little and developed into the

modern nuclear family. From the eighteenth century on, privatisation of

the family became visible in all areas of life, for example in architecture.

The modern house with its different rooms and corridors was established.

New courtesy rules required elegance and respecting the private life of

others. The intimate family became a site outside the public life and

work, a site for recreation. Public life was reserved for active men and

the private sphere of the family for women and children.

The hierarchical separation of the private and the public can also be seen in the history of art. First, art lost its connection to the ritualistic, then to the court, and finally became a special field of philosophy. Hierarchies in the art institution were also created, the highest forms of art being architecture and sculpture, suitable for the male artist who was allowed in the public sphere. Of course, the hierarchy concerned also the motifs.

To

put it roughly: Women artists, outside the public life and art academies,

were left to depict domestic motifs whereas the male artist was able to

wander freely on the streets of the modern city. So, historically, the

private and the home has been the site for women both physically and artistically.

Home and private have been defined as feminine which has remained the

condition of difference against which authentic masculine creativity has

defined itself in artistic creation. Even today, sculpture seems a very

masculine field of art. And not so many male sculptors sculpt the everyday

– not to mention sewing which is the method Kimmo Schroderus is making

the use of. Schroderus started his career in 1989. He made performances

dressed in the clothes he had sewn himself. “Sewing seemed a very

natural thing to me, I could never find any clothes that fitted me,”

195 centimetres tall Schroderus explains and continues:

“Having sewn

so many years already, it was nothing special to adopt the method to my

artistic work as well.” Indeed, if one thinks about it, there are

many similarities between sewing and sculpting – for example, they

both concern creating three-dimensional constructions in space.

The tradition of art history has remained the tradition with the women in their own special, separated compartments. Feminist art historians have tried to valorise practises and procedures that lack status in the canon of the Art, for instance art made with textiles or needlework, embroidery etc. These areas have exposed the troubled nature of the tendency of western art to valorise its fine art culture above all others by hierarchy of means, media and materials. It has been more culturally advanced to make art with pigments and canvas, stone or bronze than with for example sewing machine. Recent feminist study has argued that textile work have always been the site of profound cultural value beyond mere utilitarian usage and the site of the production of meanings that cross culture as a whole, from religious to political to moral and to the ideological.

Thus, the hierarchical division between the so called intellectual and manual art forms, between creative and decorative practises has been challenged. Feminist art historians have shown that despite of the art of embroidery was once the most valued cultural form of medieval ecclesiastical culture, it was deprofessionalised, domesticated and feminised. This example shows the relativity of our cultural valuations and their gendered nature. In this sense, Kimmo Schroderus is a paradox as a male artist and especially as a sculptor. He has worked through his whole career with materials, methods, and motifs that are conventionally downgraded because they are considered domestic, decorative, or utilitarian. Our culture characterises these attributes as feminine, and thus as less valuable.

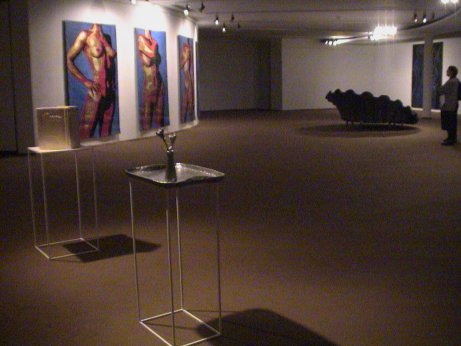

Schroderus has also been criticised for being too decorative but even so – he has continued working with the sewing machine. Actually, Schroderus first became known for with his leather-appliqués of tattooed people. In his hands, sewing became an accepted, artistic method. The leather appliqués are portraits of women and men, who have decorated their skin with everlasting images. These appliqués are technically excellent examples of Schroderus’ craftsmanship. They represent portraits of the artist himself, and of a snowboarder, an eccentric, a bookkeeper, a tattooer and a photographer. The viewer may find references to different layers of cultural production, from the traditional appliqués to the spirit of Finnish National Epic Kalevala and Akseli Gallén-Kallela to fashion and to the imagery of tattoos and piercing. Another series appliquéd in leather depict eroticised female torsos. Schroderus calls them Four Women With The Attitude.

The art of Schroderus transgresses boundaries between handicraft, high art and popular culture. For sure, Schroderus can be linked to the famous male artists of the history of art – to Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, and Jeff Koons. At the same time art works of Schroderus refer to the tradition of handicraft through his decorative use of materials and craftsmanship. In his hands black leather together with bright coloured leather, like red, gold and blue, create visually and aesthetically pleasant and beautiful surfaces. The leather appliqués can be interpreted as the people in the family environment Schroderus is creating. As their companions, Schroderus has sculpted a Series Of Eleven Mirrors.

Technically,

they are a combination of photographs and spy mirror with decorative frames.

They function as beautiful objects on the wall, but as soon as the light

is switched on, the mirror becomes transparent and exposes eroticized

encounters of two people. In comparison to the leather appliqués,

the couple in the photographs appear more fleshy and Schroderus seems

to examine the human form more closely.

The mirrors are ambiguous, they

can be interpreted as the basic furniture of every home.

At

the same time the use of spy mirror thematizes the voyeurism of our culture.

The voyeuristic tendencies of the viewer – her or his will to see

– are underlined in the act of looking. She or he must really peep

into the image in order to see the erotically charged and intimate situations

of the couple and their sweaty bodies.

From the portraits and mirrors

Schroderus moved into the space and sculpted a home for them. He created

decorative, furniture-like sculptures. First he made a steel bed covered

with leather. The shell-like, bridal bed called Sweet Dreams means the

fulfilment of the romantic love for Schroderus. It can also be seen as

the cradle of future hopes and dreams. After Sweet Dreams, Schroderus

continued sculpting the everyday. He moved on to the details of daily

life and sculpted a cherry wood table Because I Say So, two chairs called

What, a diary for two, a tray, and a set of drawers.

All

of these sculptures move in the boundaries of high art and utility articles.

Even though the sculptures are made for a couple, Schroderus does not

idealise the day-to-dayness of family life. He knows that the romanticism

of the bridal night and the hopes and dreams for the future are often

forgotten in the course of ordinary life. Especially the three-times demolished

and re-built table Because I Say So refers to the often silenced taboo:

domestic violence. In his latest art works, Schroderus has moved from

sewing and decorativeness to more traditional, masculine sculpting.

Despite

of the shift in aesthetics, his themes have remained partly in the depiction

of the daily life. He has made a car, If Not Today Then Tomorrow. The

intimacy of home opens up and the car becomes a liminal space between

the private and the public spheres. The car becomes a vantage point from

which the artist can begin to engage with other areas of art. The car

becomes a threshold which opens various routes to the field of sculpture.

One route seems to be a move from the decorative and realist depiction

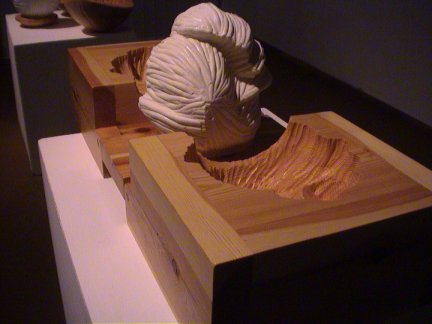

to the more abstract forms. This is present in two box-like pine and silicone

sculptures. Their names boldly state: I Was Curious. The artist, having

created a setting for home and private life, now moves into the mind of

the inhabitant.